WHO’S REALLY EXEMPT FROM RENT CONTROL? A Deep Dive Into Washington’s Affordable Housing Agenda

THE PARADOX OF EXEMPTIONS

If rent control is designed to protect the most vulnerable, why are subsidized housing providers, the very ones housing those populations, exempt from these policies? Rent control has been positioned as a solution to housing affordability, aimed at shielding tenants from spiraling rents. But when you examine the framework, a critical inconsistency emerges: subsidized housing providers who house low-income and vulnerable tenants are exempt from these same policies. This article explores why these exemptions exist, who benefits from them, what they reveal about legislative priorities, and whether rent control is truly about affordability or something else entirely

.

THE EXEMPTION BREAKDOWN

What the Law Says

Washington’s proposed rent control policies, HB 1217 and SB 5222, explicitly exempt subsidized housing providers, including Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) projects, public housing, and nonprofit-owned affordable housing. The rationale behind this exemption is to incentivize private investment in affordable housing by ensuring financial feasibility.

At the same time, these bills argue that rent control is necessary because of an affordability crisis that is devastating Washington renters. This contradiction raises serious questions about who is truly impacted by these policies and who benefits from the exemptions.

The legislative intent language in HB 1217 and SB 5222 frames the reasoning behind rent control efforts:

"The legislature finds that:

- The state is in the midst of a housing affordability crisis. Homes cannot be built fast enough to meet the urgent need to keep families, seniors, and all Washington renters housed.

- Residential rents and manufactured/mobile home lot rents have increased at a rate that outpaces inflation, wage growth, cost of living adjustments for programs like social security, and other standard economic metrics that drive price increases.

- Tenants in residential and manufactured/mobile home settings are subject to not only excessive rent increases, but also to the addition of new recurring or periodic fees that can have the effect of drastically increasing monthly housing costs."

"The legislature declares that failure to act urgently to protect Washingtonians from excessive rent increases will result in continued harm for millions of residents, especially when considering the essential nature of housing."

If lawmakers truly believe that "failure to act urgently" will harm millions of residents, then why are the very organizations housing these vulnerable populations granted an exemption from rent stabilization policies?

These carve-outs ensure that subsidized housing providers operate outside the constraints imposed on private rental providers, raising significant questions about equity and fairness in Washington’s rent stabilization efforts. If rent control is critical to affordability, why is it not applied uniformly across the housing market? The answer lies in who benefits and who bears the financial burden of these policies.

THE CONTRADICTION IN THE NARRATIVE

The Reality: A Two-Tier System

Exempting subsidized housing providers completely undermines the stated goals of rent control. These providers can and do raise rents within their regulatory frameworks, often outpacing increases imposed on private rental providers.

What makes this even more glaring is that the Spokane Low Income Housing Consortium (SLIHC) and the Housing Development Consortium (HDC) both work extensively with transitional and emergency housing providers, operating under the Housing First model. Their role is to house individuals experiencing homelessness in temporary units while they transition to permanent housing—permanent housing that is often provided by mom-and-pop rental operators and private housing providers like RHAWA members.

SLIHC represents a network of nonprofit housing providers in Spokane, focusing on affordable housing development, transitional housing, and partnerships with local governments. HDC, based in Seattle-King County, is a powerful coalition of nonprofit developers, public agencies, and private sector allies that shape regional housing policy and direct millions in taxpayer-funded subsidies to affordable housing projects. Both organizations advocate for Housing First initiatives, relying on private rental providers to absorb their program participants while securing direct subsidies and financial protections for their own operations.

And yet, both HDC and SLIHC have endorsed rent stabilization in Washington, as evidenced by their inclusion on WLIHA’s list of stabilization endorsers.

At the same time, these organizations are lobbying for increased taxpayer funding to offset rising operational costs. According to SLIHC’s policy recommendations for the 2025 Legislative Session:

- Operating expenses for subsidized providers have increased by 30.3% from 2019 to 2024.

- Insurance costs have increased by 75% over just the last two years.

- Nonpayment of rent has skyrocketed, with tenant arrears increasing 210% from $473 to $1,464 per tenant.

SLIHC itself admits:

"Funders and investors in affordable housing require project sponsors to demonstrate long-term financial feasibility of projects. Rising insurance costs and lower revenues are required to be built into these models, and investors are adopting more conservative underwriting requirements to protect against this risk. It was common for investors to require projects to generate 110% of the revenue necessary to cover projected expenses; however, investors now require projects to demonstrate they will generate 125% of the revenue necessary to cover projected expenses. In many cases, this makes projects infeasible, especially those that serve households with the lowest incomes or those experiencing homelessness."

If subsidized housing projects cannot survive without ensuring revenue growth, then why is the private market being forced into policies that do the opposite? While HDC and SLIHC push for government protections and financial safeguards for their own properties, they support rent stabilization policies that impose financial constraints on private landlords—without offering similar relief. This two-tiered system artificially disadvantages private rental providers, making it harder for them to remain in business while subsidized housing providers benefit from targeted financial incentives and program funding.

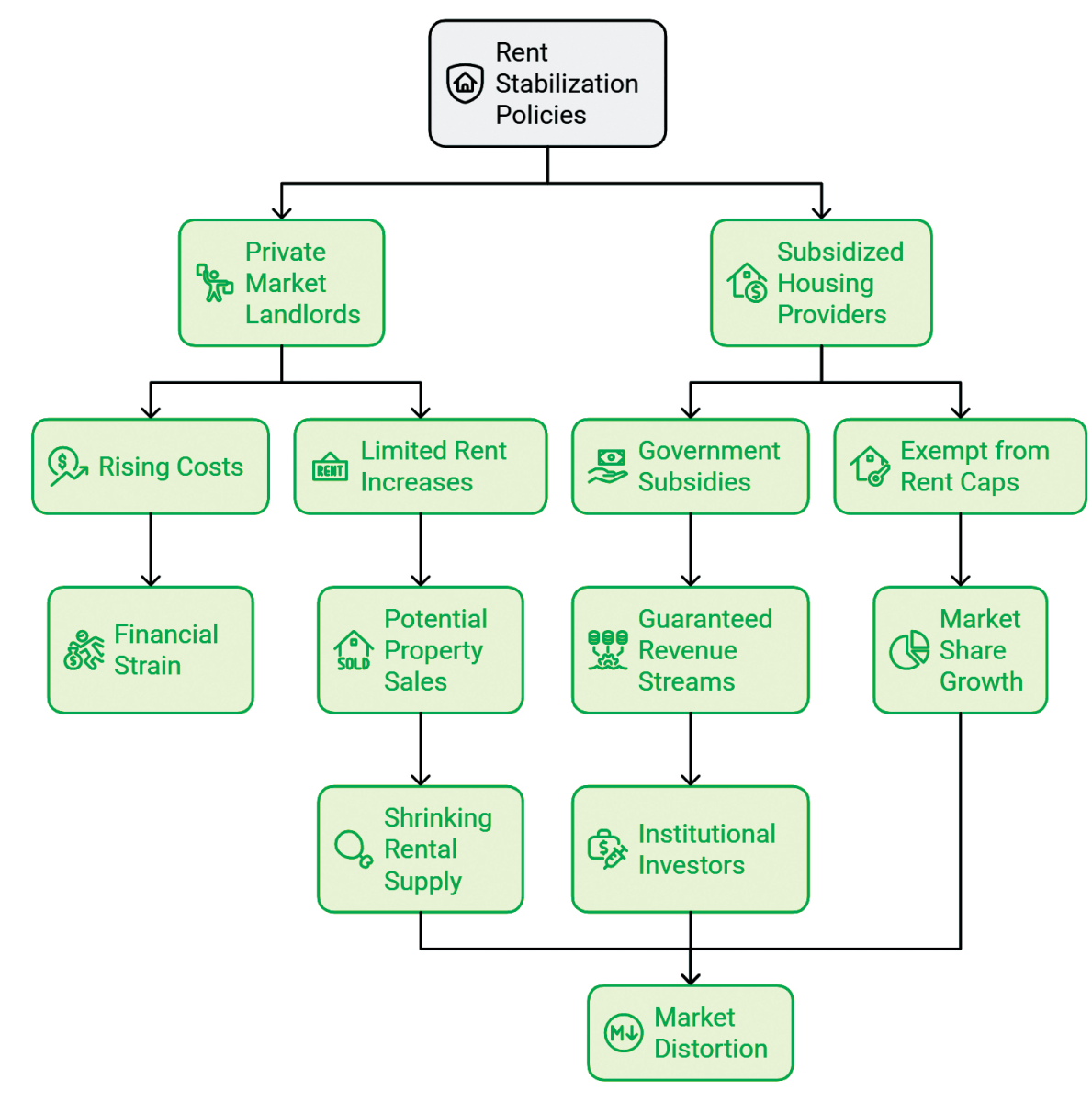

Two-Tier Rent Stabilization System

This flowchart illustrates how rent stabilization policies create a two-tier system, where private market

landlords face increasing constraints while subsidized providers benefit from exemptions, subsidies,

and market share growth. This imbalance leads to market distortions and exacerbates the housing crisis.

THE IMPACT ON RENTAL HOUSING PROVIDERS AND THE RENTAL MARKET

New Construction and Permanent Exemptions

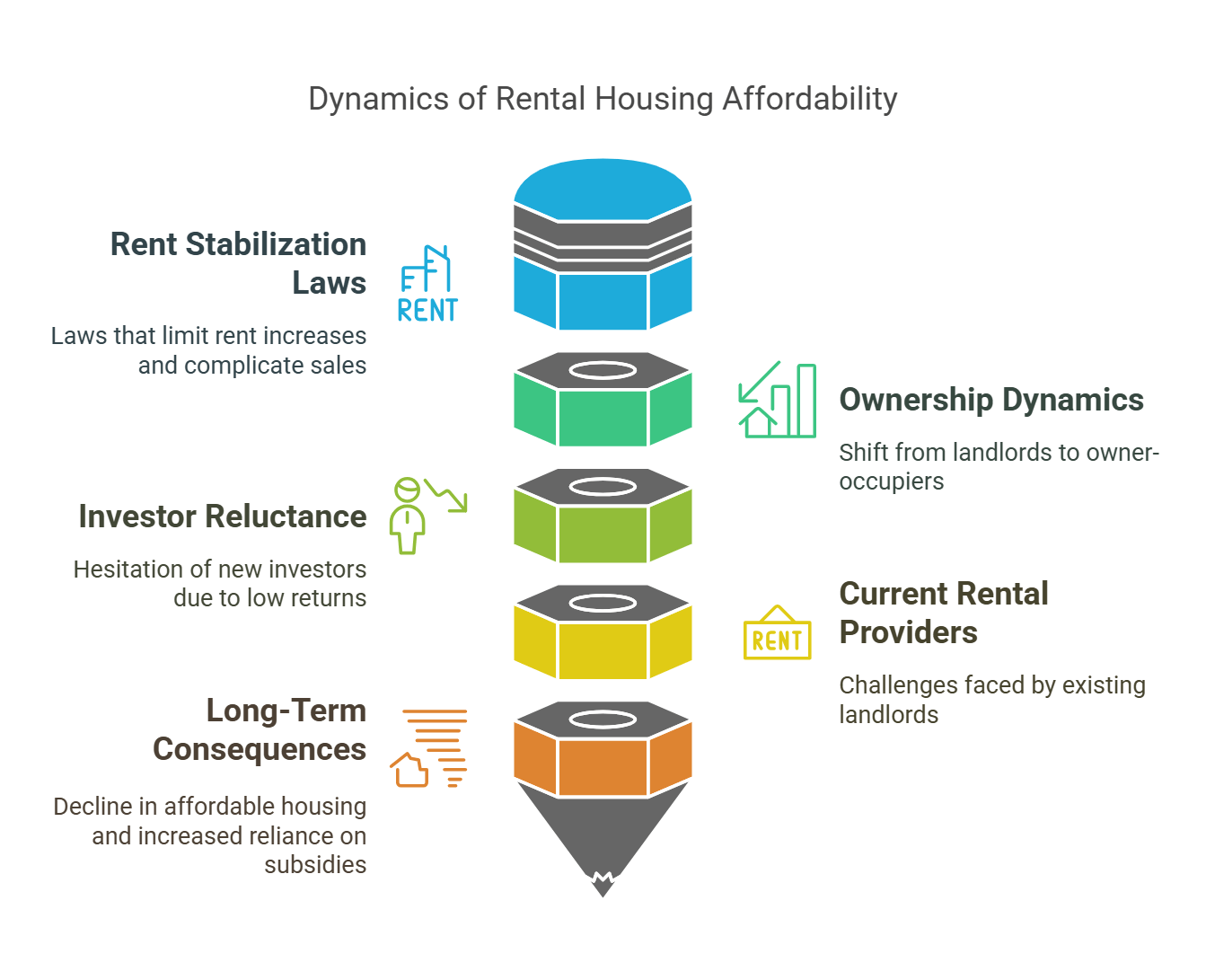

New construction is exempt from rent stabilization for ten years from the first certificate of occupancy. However, the real issue is who else is permanently exempt—subsidized housing, affordable housing developments, and politically connected entities. The affordability crisis isn’t just about building new units; it’s about who owns them and what happens to naturally occurring affordable housing.

The Affordability Dilemma

A rental home purchased in 1990 is naturally affordable today due to the long-term stability of its rent. However, if the current owner decides to sell, the new owner is faced with the necessity of charging significantly higher rents to make the investment financially viable. This situation creates a disconnect between the historical affordability of the property and the current market demands.

The Challenges of Selling Under Rent Stabilization

Rent stabilization laws complicate the selling process for existing rental properties. New investors are often deterred from purchasing these properties because they would be required to maintain artificially low rents, despite the increased purchase price. This regulatory environment makes it nearly impossible for landlords to sell their properties to other investors, as the financial returns do not align with the current market conditions.

Shift in Ownership Dynamics

As a result of these challenges, small landlords are increasingly opting to sell their rental properties to owner-occupiers rather than other housing providers. This trend contributes to a shrinking rental supply, as properties that could have remained in the rental market are instead converted to owner-occupied homes. The reduction in available rental units exacerbates the housing crisis, particularly for low-income tenants.

The Reluctance of New Investors

New investors are hesitant to enter the rental market under these conditions. The inability to raise rents to match modern property values and capital costs makes it an unattractive investment opportunity. Consequently, the influx of new capital into the rental market diminishes, further constraining the availability of rental housing.

The Trapped Rental Property Providers

Current rental providers find themselves in a precarious position. They cannot sell their properties without incurring a loss due to the disparity between the purchase price and the rental income they can legally charge. As a result, many providers choose to hold onto aging rental stock, leading to a gradual deterioration of these properties. This stagnation not only affects the property provider but also impacts the quality of housing available to tenants.

The Long-Term Consequences

Over time, the combination of these factors leads to the destruction of naturally occurring affordable housing stock. As rental properties decline in quality and availability, tenants are increasingly pushed into government-subsidized housing systems. This shift creates a reliance on public assistance for housing, which can strain government resources and limit options for those in need.

THE LONG-TERM CONSEQUENCES OF RENT CONTROL

A 2023 study, The Effects of Rent Control in St. Paul, examined the economic impact of St. Paul’s strict 3% rent cap enacted in 2021. Using parcel-level transaction data, researchers found that rent control not only failed to achieve its goals but actively worsened the housing crisis. The study’s findings highlight the unintended consequences of such policies:

- Real estate values declined by 4.4% to 5.8%, with apartment buildings suffering over a 13% drop in value.

- New housing construction plummeted, as developers were discouraged from investing in rental housing.

- Higher-income renters benefited more than lower-income renters, revealing the regressive nature of rent control’s impact.

- Rental providers were incentivized to convert rental properties into owner-occupied units, further reducing the already limited supply of rental housing.

This isn’t a hypothetical scenario—it happened in real time in a U.S. city. The data from St. Paul provides a cautionary tale for Washington policymakers. St. Paul’s rent control ordinance, like Washington’s current proposals, not only failed to improve affordability but actively made the crisis worse.

The study’s findings demonstrate that rent control, despite its good intentions, often leads to reduced investment, shrinking supply, and distorted market dynamics. These outcomes ultimately harm the very people the policies are intended to protect, leaving renters with fewer options, deteriorating housing stock, and increased reliance on government-subsidized programs.

Washington must learn from St. Paul’s mistakes and avoid implementing policies that stifle investment and exacerbate the housing crisis under the guise of affordability.

THE PATH FORWARD: A CALL TO LAWMAKERS

There is no reason to impose rent stabilization on any housing provider, private or subsidized. If affordable housing projects must meet specific revenue requirements to stay viable, why wouldn’t the same principle apply to private market rental housing providers?

RHAWA supports building more affordable housing. Washington needs a massive expansion of housing at all income levels. But this should not come at the expense of the private market, which provides the real-life affordable housing that Washingtonians rely on, not just the “affordable housing” that subsidized loans and their investors want.

Somewhere, someone isn’t telling the truth about why these policies are being pushed. The data contradicts the narrative. The science shows that rent control discourages housing production, worsens affordability, and creates systemic inefficiencies and market distortions.

"One of the great mistakes is to judge policies and programs by their intentions rather than their results." – Milton Friedman

Washington lawmakers must decide: will they create policies that actually increase housing supply, or double down on failed systems that shrink it? The choice should be clear.

This article was written and edited by RHAWA representatives and is intended for the use of RHAWA members only. Copyrighted members-only materials may not be further disseminated. Formal legal advice and review are recommended prior to the selection and use of this information. RHAWA does not represent your selection or execution of this information as appropriate for your specific circumstance. The material contained and represented herein, although obtained from reliable sources, is not considered legal advice or to be used as a substitution for legal counsel.